Continuous copper casting and rolling machine, Fuji Factory (2014)

Episodes in Yazaki’s development and business growth

This section presents episodes describing Yazaki product development,

through which our predecessors brought wire harnesses and many other flagship products to the world.

HOME Episodes in Yazaki’s development and business growth Achieving independent copper melting capability by boldly removing the old furnace before the new one comes on line

Electric wires

Achieving independent copper melting capability by boldly removing the old furnace before the new one comes on line

An achievement long in the making: Independent copper melting

The Second World War ended in August of 1945. Yazaki—which had begun making wire harnesses (W/H) early in Japan’s Showa era (1926–1989), and had successfully expanded its business as Yazaki Densen Kogyo K.K. since 1941—lost its head office and Oku Factory in Tokyo’s Kita Ward to the firebombing. In the devastated ruins that were scattered throughout Japan, no electric wires existed to build even simple temporary housing. Having lost its W/H customers, Yazaki’s near-term business would have to center on ordinary electric wires. Before long, however, Japan’s automobile industry began rapidly rebuilding itself. And in 1949 Yazaki ceased manufacturing ordinary wires and returned to being a W/H specialist.

The company’s founding president, Sadami Yazaki, was aiming high. Although Yazaki was the top manufacturer of W/Hs, the supply of copper wires continued to be monopolized by major metal companies. Sadami believed that his company’s growth depended on its gaining the ability to melt copper independently. Directing young employees who had just graduated from university with metallurgy degrees, he successfully installed a ten-ton reverberatory furnace (an electric copper melting furnace) into the Numazu Factory in 1951, just two years later. However, the furnace staff was really just a group of amateurs. When they began copper melting tests with constant reference to the instruction manual, nothing worked as expected. One time they set the burner too high and ended up splattering ten tons of copper all over the area. Eventually, after a long struggle, they finally reached the point where they could put the furnace into actual operation, albeit with considerable loss. And even after three years, they still could not produce copper of consistent quality.

“There are limitations to what open-hearth furnaces can do.” Copper melting furnaces became a nagging headache for Sadami.

Installation of a new furnace, and dismantling of the old one

While on a European observation tour in 1956, Sadami learned that there was a superior rotating copper melting furnace called a “Thomas Furnace” in Germany, and he immediately set out to see it. The Thomas Furnace could produce 300 tons of melted copper a month. It could also melt copper scrap.

“This is what I want,” he said.

Upon returning to Japan, Sadami ordered two young copper melting technicians to go to Germany, study the Thomas Furnace inside and out, conclude a purchasing agreement, and personally make sure that the furnace was loaded onto a ship. Then, just a few days before the furnace was scheduled to arrive at the Numazu Factory, Sadami said something astonishing.

“Dismantle the open-hearth furnace. We mustn’t think that we’ll be OK with the old furnace if the new one doesn’t work. We cannot go back.”

Everyone went pale. There would be no way back if they failed. The tension this realization produced was immediately felt in the factory and throughout the company. All of Yazaki was on edge.

Full-scale entry into the electric wire business

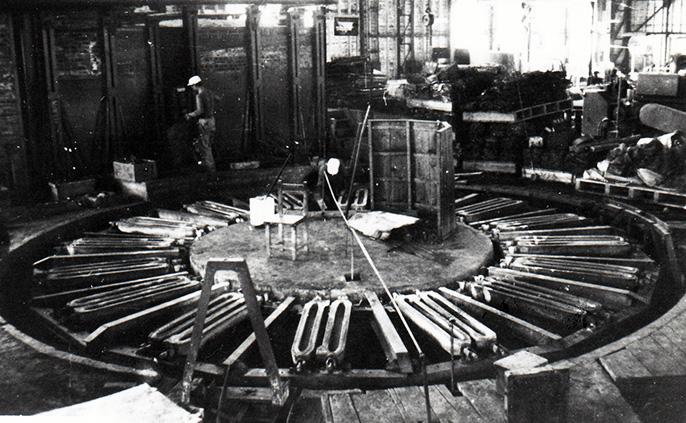

Installation of the Thomas Furnace proved tricky. A continuous casting and rolling machine that was installed with the furnace did not function properly. On top of that, the open-hearth furnace had been dismantled and was no longer available. The factory had no option but to get the system it had into operation.

Then, at the end of 1957, the day finally arrived. Sadami and his technicians, who had struggled with the furnace almost around the clock day after day, held their breath as the furnace opened. Then bright red molten copper splashed out. The rushing stream flowed to the casting and rolling process and finally emerged as lot wire.

The factory erupted with shouts of “Banzai! Banzai!” as everyone embraced each other. Sadami’s eyes were moist with tears.

The Thomas Furnace was capable of producing far more than was needed for W/H production. Moreover, the quality was showing remarkable improvement. Vinyl electric wires were developed as part of an effort to utilize this excess capacity in new products. The results of long years of research on W/Hs were put to use here. However, despite enthusiastic efforts to sell the new product to power companies and other users, established companies did not readily open their doors to this upstart in the business. Nonetheless, Yazaki’s wire salespersons doggedly visited potential clients day after day. It was during this time that numerous legends about their struggles—about “contracts for one meter of wire”—that continue to be told were born.

It goes without saying that the Thomas Furnace was also immediately dismantled when a next-generation DFP furnace (oxygen-free continuous casting and rolling machine) was brought in to replace it in 1970.

EPISODE SELECTION

EPISODE 01 Aroace: Overcoming obstacles buoyed on the founder’s adventurous spirit

EPISODE 02 The egg lays the chicken: The secret story behind the birth of the wire harness

EPISODE 03 A drum business that conserves valuable wood resources and recycles waste plastic

EPISODE 04 “LP10”: The gas meter that changed how people think about propane

EPISODE 05 Moving toward a sustainable future as a pioneer in the use of solar heat

EPISODE 07 From the quagmire of labor dispute rose the grand flower of the meter

EPISODE SELECTION